Self Titled

An unmarried woman walks into a bar

When I leave for work in the mornings, I mentally prepare myself for an encounter with The Neighbor.

It’s gotten worse lately. The old woman who lives next door to me is more unwell than ever, and spends her mornings banging on all the doors in the hallway and screaming. Sometimes she pleads for help like a child, other times she shouts obscenities at no one in particular (“Margaret you fucking whore, you jealous bitch!” To my knowledge, no one named Margaret lives here.).

It’s upsetting, to say the least. But she has a full-time nurse who caters to her and she refuses any material offers of help. When asked if she’d like to go to the hospital, she waves her hand dismissively. “It’s a spiritual problem,” she says. Essentially: You wouldn’t get it.

So, I try to ignore her. But she keeps her front door propped open during her waking hours, which means I’m put face to face with her terrifying hoarder-like apartment whenever I come and go. So I keep my head down, turn the key in the lock, and attempt to make my way to the stairs without drawing her attention, tip toeing around like I’m in A Quiet Place.

Sometimes, this works. Other days I get a “Can you come in and sit with me?” or “What time are you coming back?” or even, on the rare occasion, “Drop dead!” But last week, she hit me where it hurt: “You never help me, you spinster.”

I burst out laughing. Spinster? Look who’s talking, I wanted to say. But there’s no real use in beefing with a house-bound, mentally ill 80-year old woman who can barely feed herself.

As much as I hate to admit it, the comment genuinely rankled me. It’s true I am 32 and single. It’s true that the only man who’s visited my apartment is my ex-boyfriend, who dumped me back in July. But I like being on my own. I still have plenty of time.

Don’t I?

I first had the idea for a version of this Substack back in 2022 when I was alone in Barcelona for my yearly sabbatical—a long weekend of wandering familiar streets, flirting with bartenders, and meditating on my desires.

I had, as people had been telling me to do for years, wanted to start writing down all of my dating stories from over the years. Spinning something light and funny and even insightful out of a decade spent sitting dutifully at dive bars or waking up on unwashed sheets.

The name itself, Soltera, which is Spanish for a single/unmarried woman, came to me in the afterglow of an afternoon spent in bed with a handsome Brazilian man I had met on Tinder a day earlier, with whom I had spent hours trading multilingual sexts. I was alone in Barcelona for the first time since I was 20; I had a bright and clean apartment all to myself that had tall windows looking out onto Tibidabo.

When the Brazilian finally left, I opened the windows and went out onto the balcony where we had earlier been smoking his hand-rolled cigarettes. Cars sped lazily on the street below, dappled in early autumn sunlight. The air smelled of freshly baked bread. I still felt the gentle pressure of his hands between my thighs, and I could hardly remember a time I had felt so at peace and so in my body at the same time.

I opened my laptop at the dining room table and poured a glass of red wine, thinking about how I’d use this story as an introduction to my concept: a cannibalized version of my own experiences, led fearlessly by a character who was delighted by her aloneness. I’d present the boldest, most self-assured version of myself—the woman who feels most alive while drinking a martini alone at a steak dinner, who never worries about getting a text back. I’d trim all my insecurities and regrets (boring!) and become a spokesperson for lonely single women, saying: I’ve been through the meat grinder of men and I found something better on the other side.

But that bravado began to wane as the days went on. Remote work obligations began to eat at my time, forcing me to early dinners in empty restaurants. The Brazilian replied to me sporadically, promising a second meetup before I left, only to ghost me completely. I spent the week chasing a text back and some sort of confirmation from the universe that I wasn’t just wasting my time, neither of which arrived. My writing became stilted and bitter. I found myself saying something else to my imaginary audience instead: Yes, you too can try and trick yourself into believing your life can be beautiful and exciting even if you never, ever get what you really want.

So I put the project aside. When I picked it back up again, it had, of course, become something else. I had too.

In my high school Spanish class we read an abridged version of Don Quixote. We would take turns reading chapters aloud, painstakingly picking apart the verb tenses and the vocabulary: caballero andante, molino, rescatar.

The story, for anyone not familiar, is a metafiction about a middle aged man who lives a quiet life in the countryside. But he’s obsessed with chivalric novels involving knights, princesses, and daring heroics, and soon his fantasies turn to madness—he then believes himself to be a knight errant, and sets out on adventure to battle monsters (windmills) and rescue a damsel (a local butcher woman).

The long-winded descriptions of his journey all blended together for me, but I remember thinking the ending was sad: Finally, after years of being happily ensconced in his delusions of grandeur, Don Quixote falls ill and takes to his bed. When he wakes up, he’s himself again. He has no desire for adventure; he sees everything exactly as it is—the windmills were only ever windmills, nothing more. He vows to never get caught up in that kind of fantasy ever again.

I have always been embarrassed by my desires. There is, I felt even as a child, shame in wanting. Not because of the fact that you might not get what you want (I’ve always wanted things I couldn’t have because of their unattainability) but the act of being seen wanting.

I also felt the constant push and pull of my soft Pisces heart—desperate for romance and full of tender dreams of the future—at odds with my inherent pragmatism. Any time I found myself fantasizing about falling in love, I could sense generations of stoic Irish women rolling their eyes, reminding me: You are owed nothing, you should expect nothing. This is real life, not a fairytale. Get a grip.

So I tried to give up on love before it ever happened to me.

I remember in middle school or early high school I began to experiment with an idea. What if it didn’t happen? What if I never met anyone that I liked or who liked me back, never got married? Could I live with that?

Of course, at the time I still had braces and was more immediately concerned that no one would ever want to put their tongue in my mouth or ask me on a date to get pizza or ice cream (things that did indeed come to pass, despite my anxiety). But every now and again I microdosed a sort of romantic fatalism, trying on the feeling of ending up alone. Not even imagining rejection, just a blank future devoid of partnership, almost as if I were a member of a remote, uncontacted tribe who had never even heard of romantic love and didn’t know it existed.

It’s possible, and I stress possible, that such a moment may never come: you may not fall in love, you may not be able to or you may not wish to give your whole life to anyone, and, like me, you may turn forty-five one day and realize that you’re no longer young and you have never found a choir of cupids with lyres or a bed of white roses leading to the altar.

-Carlos Ruiz Zafón, The Angel’s Game

But once I got comfortable with that idea, life had its own plans. Inevitably, as anyone could have predicted, I did meet people that I liked who liked me back, I fell in love, I had all the experiences that I had worried at 14 might never happen to me, and plenty more experiences that I couldn’t have even imagined or articulated back then.

For a while, these lived experiences restored my faith in romance and spurred me to search in earnest for love in all its iterations, not even caring if anyone saw me yearning for something that wasn’t guaranteed. Famously, I spent the years out of college dating incessantly and sleeping around. While I had done this without much intentionality, and often just out of boredom or misguided self-preservation, I had, deep down, expected at least one of these encounters to turn into something real.

I wanted a boyfriend but wasn’t ready for the emotional commitment. I knew a serious relationship would mean having to beat the final boss of Being Seen. I had often picked the wrong men when I was younger just out of blind desire, but around 25 (hello frontal lobe!), I began doing it on purpose.

I dated married men in non-monogamous relationships, I lusted after coworkers and one-night-stands who gave me the absolute bare minimum, I went out with guys who told me explicitly they were hung up on someone else or could never give me what I wanted. I went along with all of it willingly, safe in the knowledge that I would never be asked to give the one thing I wasn’t sure I was even capable of giving: my entire, true self.

And, regrettably, there was a sort of smug self-righteousness to it as well. It was my own version of I’m Not Like Other Girls. See, I don’t need a conventional relationship. See, I don’t have to rely on something as silly as love for self-validation. And sometimes, I genuinely felt that way. There were moments where I realized I was, in fact, perfectly content in not committing to something, not out of fearful avoidance but because I really did just like being on my own.

But those were the moments that felt the most confusing. Was I actually happily independent or had I just spent so long telling myself that I would never have the love I wanted that I started to believe it?

I wonder what I have missed out on because of that stoic voice telling me to get a grip. It’s true that things maybe haven’t unfolded in the romantic comedy that I wished for. The revolving door of late nights and lovers that I used to cherish is long dead and lost its luster a while ago, maybe when I tried to write it into something it wasn’t.

But there is a bigger part of me that believes I’m too young to be throwing in the towel this soon, and I’m too old to be so afraid. A windmill can still be a giant if that’s what you want it to be. I don’t know why I spent so much time trying to convince myself it couldn’t.

Sometimes when I think of my past relationships with men—relationship as an all-encompassing term here—I see it in my mind as a desire path. You know these: in a park, a neighborhood, or on a hiking trail, there are places alongside the sidewalk or road where the grass or dirt has been walked over and worn down from years of people taking a shortcut. Many thousands of feet opting for convenience or avoiding an obstacle on the intended path, creating a new one of their own.

I could not walk the straight line of college sweethearts and committed monogamous relationships that was laid out before me when I was younger. So I took the long way around.

My late 20s and early 30s were a slow transition from the constant thrill-seeking and bed-hopping to sporadic, intentional dates and, more often than not, evenings spent dining out alone with just my thoughts to keep me company. For a while, it scared me that it seemed like I had lost my appetite for excitement. My friends still thought of me as someone with an insatiable libido who was willing to chase after anything if it made for a good story (i.e., “We fucked a group of guys from Penn State and we’ll fuck you too!”), and I didn’t try and change their perception because I didn’t know how to be someone else. But that didn’t feel like me anymore.

And the worst part of me began to worry—the shame of eating the birds—that all my years of hedonism had become a stain somehow. How could someone meet me now and love me, knowing where I had been? Not to mention the other side of the coin: was I boring now because I had rejected what seemed, at least to other people, a core part of my personality?

It was easy to backpedal to that old, self-abandoning thought pattern: You are owed nothing. You will not get what you want. Embarrassing of you to want love in the first place!

But by 31, that voice had started to sound shrill and insecure. That winter I decided to silence it for good. At Christmas I announced to anyone who would listen that I was finally going to get a boyfriend. The time had come, I said. I wasn’t afraid anymore (I was). And by the spring, it happened almost as easily as just speaking it into existence.

Love comes quietly,

finally, drops

about me, on me,

in the old ways.What did I know

thinking myself

able to go

alone all the way.-Robert Creeley, “Love Comes Quietly”

Love did indeed come quietly, as it usually does. Part of getting older has been realizing that so many of the big things I imagined as a child—back when I was disaster prepping for a life in which they might never happen—have not been earth-shattering or even particularly remarkable on paper. They’ve all been perfectly ordinary moments made special only because of the people who were there.

Over the summer I watched my oldest friend get married in Seattle. When it was time for the ceremony, her dad drove us from the AirBnB where we were getting ready to the wedding venue. We sat in the car for a few moments, just the two of us, laughing about how crazy it was that only a split second ago we were carpooling to basketball camp and playing Neopets on her family’s desktop computer. I remember looking at her in the passenger’s seat in her white dress, seeing instead the tiny five year-old girl in an oversized backpack that I had loved my whole life, and thinking how shockingly normal and inevitable the whole thing felt. The big wide future arriving as smoothly as a car pulling into a driveway. What did I know thinking myself able to avoid it entirely?

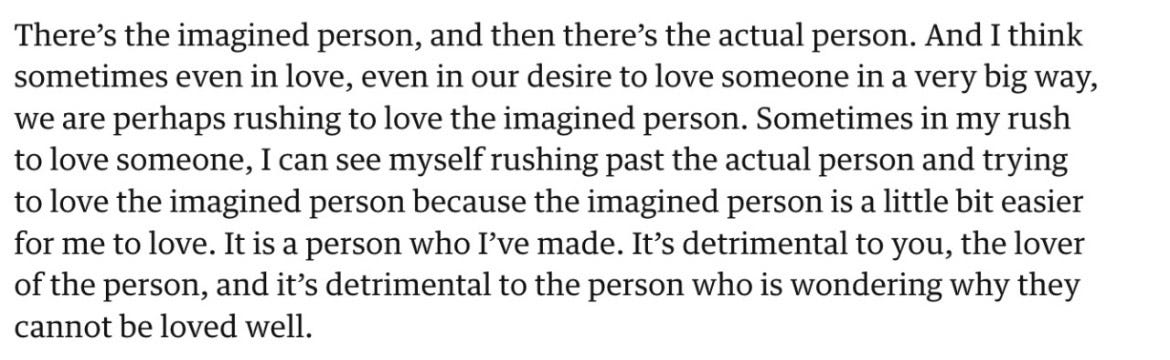

The childish part of me sometimes still craves the fantasy. But I go back to this interview from one of my favorite poets Hanif Abdurraqib every time I feel myself lamenting the mundanity of reality:

So much of my life has been a rush to love an imagined future and an imagined person, an imagined self. So often it’s been easier to back myself into a binary, to madonna/whore myself into a caricature than to accept my own contradictions. What a relief it is to finally see the actual person out of the fog of fantasy. And if love is going to come anyway, as it always does, plainly and quietly, then let it. There’s an open barstool right next to mine.