Circles

Retracing the same paths again, naturally

I have writer’s block.

I spend all day, every day writing corporate copy—emails and advertisements and flashing screens that talk about nothing, about real estate and sales and productivity, urging people to make the most of their 9-5. A common editorial concern is copy getting “duplicative”—too repetitive, the same idea expressed the same way too many times over.

This is a death sentence for compelling marketing. But repetition is the only way I know how to write, and it’s the only way I’ve known how to live.

When I lived in a tiny 5-floor walk-up in Bed-Stuy during the pandemic, I spent most of my time on the shared roof deck. In the mornings, I’d set up a yoga mat and dumbbells on the spongy tar blacktop, and when the sun went down I’d park up there on a folding chair with a coffee mug of boxed wine or double G&T. One gray October morning, I facetimed a psychic to ask if I’d ever escape the small, stale bedroom that had started to feel like a prison or the rotation of unavailable men that would light up my phone in the middle of the night.

She told me then then what I already knew: that she saw my life as a series of circles, like exits ramps perpetually looping on a long highway. That in all my years, I would always feel like I was repeating the same patterns. Someone else later described the same image to me in a more optimistic light: Going up a mountain in a winding spiral—ascending, but tracing the same paths nonetheless.

I find this time of year difficult. February, to me, is a Death month, always has been since that day—ten years ago now—when everything twisted into something new and strange. It’s a frozen tundra of a month, one where I walk backwards and find myself in the same places: kneeling in the carpeted bathroom of a Times Square office, crossing 6th Avenue at dusk.

March is different, harder in some ways. My birthday is the last day of winter, the last day before spring. Blame it on Pisces season or the anxiety of party planning, but during these weeks I often feel irritable and burnt out. March comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb. It’s possible it’s that final push, the last gritty resolve of winter, that creates the restless current running underneath it all. The crocuses will be up soon. Maybe I’ll join them.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about both compound and collective grief, and it’s impossible not to talk about 2020 and the pandemic in the same context. This feels stale and cliche for some reason, and I think it’s maybe because—like I often feel about my own writing—it’s something that’s been talked about to death, analyzed and argued over to the point that it’s lost its meaning. And yet: it’s still an open wound. We just now have enough distance to see everything that happened for what it was.

During that summer1 I spent in the tiny walk-up (mostly alone and mostly drunk and certainly half-crazy) I took a fiction workshop over Zoom. I was out of practice, and I slapped together two independent short stories cobbled together from old drafts I never finished. Neither was particularly good. I had written two entirely unrelated narratives, one about a dinner party New York City, the other about a college grad coming back to a small town in the early aughts. They both had the yearning, melancholy sharpness I had wanted to imbue them with, but neither said the thing that I wanted to say, a thing I still wasn’t entirely sure of, until someone in the workshop asked,

“Did you mean to write about collective grief?”

He went on: “You have two stories of close friends suffering a single loss and changing entirely as a result of it, and having to grieve in complex, interconnected, and private ways.” That was the first time I could articulate what I had not yet had a name for; the first time I knew that it was possible to own a loss that was not my own.

When Danny died during that wet, isolated spring before the long, drunken summer, it felt like deja vu. Vampire Weekend said it best: here comes the feeling you thought you’d forgotten. Grief is like riding a bike—all the clenching and the bruising is a muscle memory, a cellular recall.

Those two deaths—now ten and five years gone, respectively—still sometimes surprise me with their weight. Some nights, sitting in the back of a taxi or alone in my apartment with a room temperature whiskey, I feel an entire decade’s worth of it knock the wind out of me. It swings into my gut like a hammer, it pulses up my spine in the dark.

I still play solitaire on my phone when I can’t sleep, and sometimes when I close my eyes I see the deck of cards being dealt out on a loop. Red, black, red. Ten, five, one. Death, and death, and death.

Wasn’t I just here before?

I’m in the process of looking for a new apartment, and not by choice. If I were to give into the urge to be dramatic, I’d say that lately it feels like I’m being pushed out of my life on all sides—that after a decade of being unbalanced and out of breath, I finally found my footing only to have the universe snatch it all back from me.

The other week I looked at a place in Bed-Stuy just a few blocks from where I spent all those months locked inside, drinking and writing and waiting. I tried to reorient myself with the neighborhood on Google Maps, virtually strolling the streets I used to walk in the empty mornings from Bedford-Nostrand through Clinton Hill out to Fort Greene park—but I got lost.

I used to know the blocks like an old rhythm: Bedford to Greene. Washington, Waverly, Clinton. Clermont to DeKalb. Now I don’t know which ways the streets turn.

When I try to recall 2020, it has the same quality as a vivid dream from a long nap. Blurred and disjointed, bright and strange and warm. It seemed like March turned into July before suddenly the gingko trees were a yellow rain. The way time moved didn’t bother me then; my grief was still drunk and aimless but not as sticky as it once was. Everything felt tender and nostalgic—and yes, sad—but I could sense the small mechanical whirrings of Change running underneath everything like a seed of hope. I surrendered to it completely. The world had ended and I had already begun to shed my skin, I was ready to meet a new self on the other side.

And I did. When the year turned, I left the walk-up behind, left the job I had outgrown, left the random men who cycled through my phone in favor of someone who took me out to dinner and made me coffee in the mornings. I moved into a bright studio all my own, next door to my best friends and above a restaurant with all the steak frites I could ever want.

Four years later, I’m packing it all up again. It seems even with all my practice rotating a deck of cards that I’m still not capable of pattern recognition—the same events happen to me over and over, and I’m surprised every time.

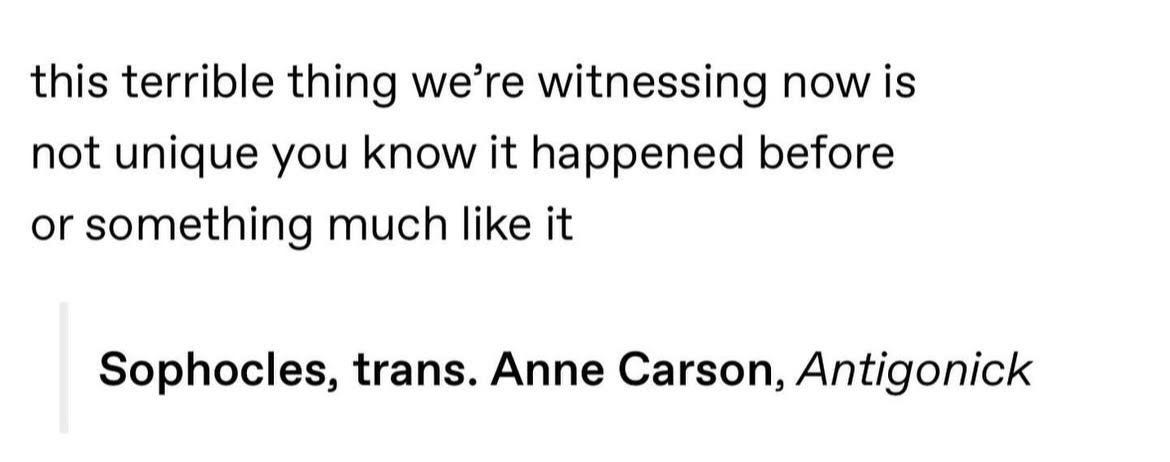

There is a trope in fiction called being “doomed by the narrative.” This is when a character’s fate is inevitable from the start—whatever path they walk will end up in the same place no matter what. Often, this ends in death (Antigone, Mrs. Dalloway, Anna Karenina)—but not always.

I like my life. Despite everything, it hasn’t been a horror or a tragedy. I don’t feel empty or bewildered the way I did years ago, and I don’t think so much anymore about ancient nights in Mexican restaurants or the front seats of cars.

But I do often feel like I am going in circles. Not doomed so much as trapped.

Sophoclean tragedy has a quality of tidiness that can be terrifying. He tucks in every stray thread. Or rather he make it seem that each of these threads was always already woven into the same net. Why did anyone think they could escape?

-Anne Carson, from the translator’s note to Antigone

I’ll say something that maybe you’re not supposed to: I am bored by grief and its familiarity. The individual loss always has its own sharpness and sting, but the underlying sensation is the same. It always feels like reaching out for something that’s not there, like missing a step at the bottom of the stairs.

Sometimes, I still miss those pandemic evenings I spent on the roof in Bed-Stuy or the early days in Astoria when everything was soaked in confusion and melancholy—and hope—and there are nights coming home in the back of a cab when I hear a familiar song that reminds me of then. And I have that same urge to reach backwards. I want a person who’s no longer here, I want a moment that no longer exists. They’re in an old loop, a circle I completed and retrace like an underpainting. A deck of cards dealt out the same way twice, three times.

But is it so bad to always end up in the same place? If I ever finally found myself outside of the roundabout of my life, the swooping exits—would I miss it? The familiarity and predictability, the circuitous nature, like a train making its turn around the Queensboro Bridge at sunset.

Perhaps the hardest thing about losing a lover is

to watch the year repeat its days.

It is as if I could dip my hand downinto time and scoop up

blue and green lozenges of April heat

a year ago in another country.I can feel that other day running underneath this one

like an old videotape - here we go fast around the last

corner— Anne Cason, The Glass Essay

It’s a strange season. I can still feel those old circles running under the present like an old VHS. In another life it’s five years ago, it’s a wet spring tunneling into a long, dark summer; and I’m ready for the end so long as it means I get to see something resurrected.

But right now, it’s still winter, and I haven’t walked away from anything yet.

When I remember the pandemic, I remember it as unfolding over the course of a single summer, though of course that’s not true. Everything seemed to happen between April and August, the rest is a blank.